Article published originally at Southwest Art | March 16, 2011

By Bonnie Gangelhoff

Dean Mitchell has been compared to Vermeer, Wyeth, Homer, and Hopper, but it’s the Andrew Wyeth comparison that always takes him aback, and perhaps with good reason. Their backgrounds couldn’t have been more different, Mitchell says. Andrew Wyeth grew up on the East Coast in a prominent, artistic family, the son of well-known illustrator N.C. Wyeth. Mitchell grew up in the South—poor, black, and not even knowing his father. His mother discouraged him from a career in art because it was too hard to make a living. And his aunt told him, “Black people will never buy pictures.”

Snow Hills, watercolor, 20 x 30.

Nevertheless, Wyeth and Mitchell do share at least two things in common as artists. Both paint in watercolor, and both portray people and places unique to their time. And Mitchell is well on his way to gaining the recognition Wyeth achieved in his lifetime. His awards have been stacking up since he was in his 20s, and he’s received more than 400 to date, including top honors from the National Watercolor Society and American Watercolor Society, the Arts for the Parks Medal for Overall Excellence, and first prize at England’s T.H. Saunders International Artist and Watercolour Show. In 2009 and 2011, Mitchell received the watercolor award in recognition of exceptional artistic merit at the prestigious Masters of the American West Show at the Autry National Center in Los Angeles. His sensitive, evocative paintings, which often use a tonalist palette, are also in museum collections around the country, including those of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and the St. Louis Art Museum.

Today, at 54, Mitchell works out of a studio in Tampa, FL, not too far from the small town of Quincy where he grew up. He finds beauty in everything, from historic whiteboard-paneled Southern churches to the faces of hard-working street musicians in New Orleans. Since his art school days at Columbus College of Art & Design in Ohio, he has been concerned with his immediate surroundings as subject matter—and he is not afraid to tackle personal and hard-to-sell images, such as a portrait of his uncle when he was dying of cancer. Mitchell describes himself as an American painter interested in contemporary subjects. “I think a lot of what I like to paint has to do with growing up poor and without a father in my life. I am always searching for a sense of place—a sense of intimacy in my work,” he says. “Sometimes that doesn’t have mass appeal.”

As this story was going to press, Mitchell was preparing for an upcoming show titled Rich in Spirit, which opens in July at the Gadsden Arts Center in Quincy, FL. The title says much about what he is trying to convey in his current body of work—the idea that even though a person may not have a hefty bank account, they can possess vast stores of inner strength and dignity. The show will include the town’s architecture and its people, including women like his grandmother, who raised him and struggled to pay the bills while working at low-wage jobs. “Poor people don’t have material possessions, but they can possess something different, like richness in spirit,” he says.

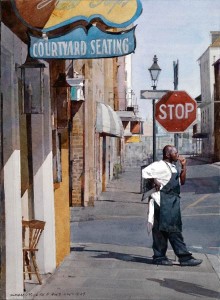

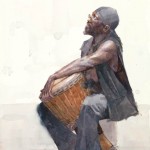

In addition to Quincy, another place that has captivated the artist is New Orleans. Mitchell first visited the Crescent City in 1984 and was immediately drawn to the atmospheric city streets and the character revealed in people’s faces. The street musicians and their prodigious skills in particular captured his attention. Horn players, saxophonists, and keyboardists he heard seemed equal in talent to the most popular and prominent musicians of the time, but the New Orleans artists just didn’t get the same recognition, he realized. Soon after his visit, Mitchell began painting the jazz men. “I think my paintings are often trying to elevate the underprivileged so I can convey a sense of their dignity and give them a voice in American society,” Mitchell says.

Waiting for Customers, watercolor, 15 x 10.

The artist has returned to New Orleans several times every year since his first visit more than two decades ago. In the aftermath of hurricane Katrina and the recent recession, he has become intent on keeping the city on the national radar. “I just want to keep the city in the forefront of American consciousness—to remind people of this great American city and say something about how the people there are hurting,” Mitchell says, referring to paintings such as SOUNDS OF THE CRESCENT CITY and WAITING FOR CUSTOMERS.

Whether it’s old buildings about to be torn down or ordinary people who go unnoticed, Mitchell says in some ways he identifies with it all, because he too knows what it’s like to feel “discarded” and experience “a sense of hidden hurt.” None of that sense of hurt is visible in his outward demeanor, though: The first thing you notice about him is that he is animated, exuberant, and positive. In fact, he often gives motivational talks to high school and university students about working hard and setting goals to achieve their dreams.

Mitchell’s earliest memory of art came when he was five years old and his grandmother gave him a paint-by-numbers set. He didn’t really like the set and soon found that he preferred drawing on his own—mainly cartoon and comic book characters like Mickey Mouse and Superman. When he was 12, he saw an advertisement in a magazine from the Famous Artist School but, when contacted by the organization, his family said they couldn’t afford the fee. After that, Mitchell recalls, he began saving his lunch money, skipping a meal to buy paintbrushes and oil paints. His interest in art continued to blossom into a passion, despite objections from his family.

After graduating from high school, he enrolled at the Columbus College of Art & Design in Ohio. He entered his first art competition and professional juried show while in his junior year there. A professor encouraged him to enter a prestigious national watercolor show, and he was juried in on his first try. A few years later, at 27, he became one of the youngest signature members of the American Watercolor Society.

In 1980, after graduation from art school, he moved to Kansas City, MO, to work as an illustrator for Hallmark Cards. After three years the company terminated his employment, but by then Mitchell knew he wanted to pursue a full-time career in fine art. He had been entering more and more contests in his spare time and winning awards. In 1981, still in his early 20s, he entered 34 contests, racking up three top prizes and $4,500 in cash—about 25 percent of his yearly salary at Hallmark. With these accolades, he was both undaunted and determined to pursue his passion. And he was also willing to live on a shoestring budget for as long as it took to make his name.

One of the first things he did was buy a book about how to invest. “I only had $1,000 to invest,” he says, “but I bought an IRA. Then I started to put the maximum into the account every year.” He moved into a one-room efficiency apartment in Kansas City and kept his Honda for 15 years until it was pretty beat-up. He continued to sock away as much money as he could as he slowly began to sell paintings and win more prize money. “The more I made, the more I figured out how to keep it,” he says. By the early 1990s one of his galleries in New Orleans was selling some of his works for upwards of $40,000.

But the road to success was not without bumps. In the beginning, many gallery owners didn’t want to represent an African-American artist, and grant money he applied for often went instead to more esoteric art projects. Early on, however, Mitchell decided to build his career and make his name by entering competitions that were color blind. “Juries are the best and the fairest way to establish yourself,” he says. “Let the work speak for itself” became his motto. For Mitchell, the strategy worked—he kept chalking up awards, which led to magazine and newspaper articles, and ultimately to name recognition.

In 2002 he was included in an exhibition titled Black Romantic at the Studio Museum in Harlem. The exhibition was reviewed by the respected New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman, and a full-page color reproduction of one of Mitchell’s figurative pieces, SOCRATES, accompanied the review. Kimmelman wrote, “Mr. Mitchell’s works are subtly tuned character studies with an eye toward abstract form and charismatic light. Mr. Mitchell is a virtual modern-day Vermeer of ordinary black people given dignity through the eloquence of his concentration and touch.”

Recently Mitchell met his father for the first time. Will his art change as he establishes this new relationship? “No, I am who I am,” Mitchell replies. Also recently, Mitchell received the top award for his contributions to the watercolor medium at the Masters of the American West show. When he stepped to the podium to accept it, he began by saying, “It’s been a long journey for me. I am humbled.” Most of the collectors, museum patrons, and other artists gathered for the presentation probably had no idea just how long and rocky that journey has been, because without saying much more to the audience, he graciously accepted the award and stepped away from the podium.

But some young high school students in Canton, OH, soon heard about his long journey. He was asked to come and share his life story just after the Masters show. When asked what he will talk about, Mitchell replied, “I will tell them to stop making excuses. Whatever your passion is, learn to master it. If decent people see you are trying, they will help you. I believe that because that is what happened in my life.”

Representation

Morris & Whiteside Galleries, Hilton Head, SC; J. Willott Gallery, Palm Desert, CA; Astoria Fine Art, Jackson, WY; Hearne Fine Art, Little Rock, AR; www.deanmitchellstudio.com.

Upcoming Show

Rich in Spirit solo show, Gadsden Arts Center, Quincy, FL, July 29-October 29.

Featured in April 2011.

Beautiful & Peaceful, New Orleans, watercolor, 15 x 10.

Bongo Drummer, watercolor, 15 x 10.

Buffalo Solider, watercolor, 15 x 10.

Damaged Balcony, watercolor, 22 x 30.

Driftwood, watercolor, 16 x 30.

Early Spring in St. Louis, watercolor, 20 x 30.

Erosion, watercolor, 10 x 15.

Grown Over, watercolor, 10 x 15.

Gulf Water Blues, oil, 10 x 15.

Midwest Mansions, watercolor, 15 x 10.

Napoleon House, watercolor, 15 x 10.

One Way Out, watercolor, 15 x 10.

Pirates Alley, watercolor.

Quality Hill, watercolor, 10 x 15.

Shawnee Barn, watercolor, 8 x 10.

St. Louis Mansion, watercolor, 30 x 20.

Sunshine, watercolor, 15 x 11.

Teton, watercolor, 12 x 30.

Urban Mass, watercolor, 20 x 15.

Violinist, watercolor, 15 x 21.

Yellowstone Cliff, watercolor, 22 x 30.